I had never been to Athens or Split, or even set foot in their respective countries, before taking part in The 5C Project. Yet, when I first heard about the project, Tirana was the one place I was most excited to visit. I may never get another shot at going to Albania, I remember thinking. And Marian Tutui, the artistic director of Divan Film Festival, and one of our mentors in this project, kept filling my head with his funny anecdotes about his earlier visits there (I remember one about luxury German cars vs. Roman time roads), and how it was “unlike anything you have seen before”.

I opened my eyes and ears wide as soon as we landed. I registered a few funny oddities – like the taxis with the Mother Teresa stickers, the Edward Hopper characters that populated the computer generated design of public works, or the fact that George W. Bush had a street named after him –, but other than this, my exotic expectations fell short.

It was just another country from the former Eastern Bloc, slowly crossing over to the West: the cuisine was Italian, the language felt strangely familiar to me (there are some common words and the pronunciation is very close to Romanian), and the people were extremely polite… nothing of the “wild wild east” from the tales of the ’90s.

But there was one thing that baffled me, and the more I explored the city, the more poignant it became: the architecture. At first I didn’t see it because I was too busy looking for the exotic, but then it became clear: Tirana is a huge Lego set, where every spare construction material is recycled, and not always for the use it was initially designed for. The result is an incredibly creative, colorful and beautiful… kitsch.

The style of the city resides in its lack of a unified style. At one point we saw a short school film made at the Academy of Film & Multimedia Marubi, that stresses the very essence of this creativity: a struggling young worker gets evicted from his flat and he makes his “home” in an unused metal heater on the roof of the building (the Tirana skyline is lined with satellite antennas and these kind of heaters). This creativity is of course also related to poor economic conditions, and it will probably soon fade into the more modern, unified architecture that is being erected all over the city.

It was again Marian the one who pointed out the ridiculousness of our travel arrangements: we had to fly to Rome, and go over the Adriatic twice, in order to travel the less than 1000 km of continuous landmass that separate Bucharest from Tirana.

Years after the days of national communist ruler Enver Hoxha, his legacy of isolationism still lingers. Our first visit was to the Albanian National Film Archive, where we learned from collection manager Eriona Vyshka, that the biggest challenges they face today can be traced back to the same isolationism. Because of the country’s almost complete shutdown of imports in the late ’70, the films were developed with using the same chemical baths over and over. Decades later, the colors are starting to fade, and there is a real danger of important films being lost forever. This is where Iris Elezi and Thomas Logoreci come in, the dynamic duo behind Albanian Cinema Project, an organization dedicated to preserving, restoring, and promoting Albanian film heritage. Their energy and tag team approach when presenting their project, results, and future plans, are enough to make you consider quitting your job and becoming a film restorer.

Two days later, we had the chance to meet them again, this time for an overview presentation on Albanian cinema. Our last day in Tirana ended with the TIFF (Tirana International Film Festival) award ceremony, where we were on jury duty and presented the awards for Best European Short and the Best European Film.

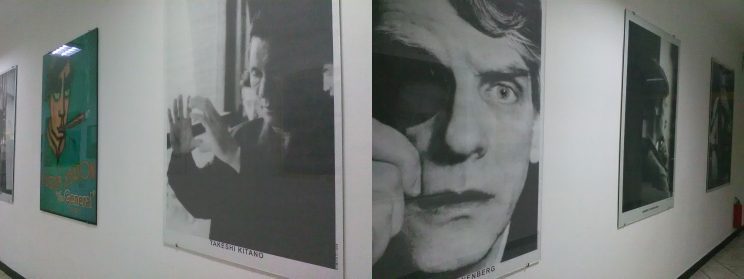

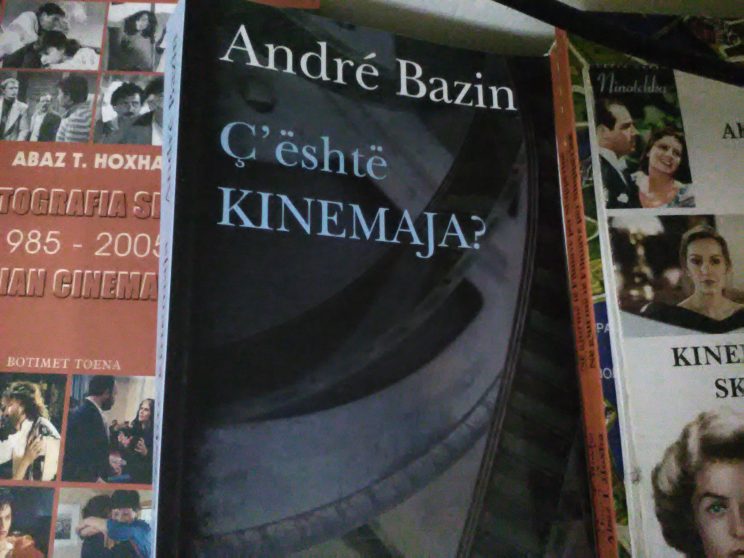

However, the ultimate highlight of the Tirana stop, and one of my fondest memories from this year long journey that has taken me all over the Balkans, was the Academy of Film & Multimedia Marubi. There, this creative approach that I kept noticing in buildings all around the city, has blossomed into the most wonderful – in terms of set design at least – film school I have ever seen. It is a private school but at the same time a living/working museum, headed and curated by Albanian director and screenwriter Kujtim Çashku. For many years, the school had been under pressure from TV businesses fighting for the lands of the old Kinostudio. Fighting through adversity, Kujtim Çashku has managed to build a functional “zen garden” of cinema, an inspiration and reminder for why we do what we do (spend our lives around films).